Selective and Diverse

A More Selective and Diverse Graduate School: 2020 to 2021

Chris Rios, Associate Dean, with David Winkler

The previous essay (A Decade of Change) compared the Graduate School’s admissions trends between 2010 and 2020 against the broader higher educational landscape. What has happened since? As we turn our attention to changes over the past year, we lose the opportunity for national comparisons. But we gain the ability to look more closely at the make-up of the new categories introduced by Dean Lyon (residential research doctorates, traditional masters, and online/professional programs). To include all our programs, which are spread across four academic calendars (semester, trimester, quarter, and accelerated), we have compared calendar years 2020 and 2021 rather than fall only enrollment.

One of the more significant but less obvious changes over the past year has been a paradigmatic shift in recruitment and admissions. Traditionally, the Graduate School has played a supporting role, most often responding to each department’s individual initiative. In 2021 we became more proactive. First, the expansion of professional programs brought new partnerships with Centralized Application Systems, which allow prospective students to apply to multiple universities with minimized effort, and integration with so-called OPMs (online program management systems) that have facilitated our rapid and dramatic growth in the professional fields. Second, we increased our PhD recruitment by providing prospective students across the United States with targeted, discipline-specific information about Baylor’s research opportunities and resources. Third, the past year marked the second in a renewed effort to enroll under-represented minority students. In this vein, we sponsored and attended national meetings geared towards minority students, collaborated with program directors to enhance their efforts, and admitted our second cohort of McNair Doctoral Fellows, a program designed to attract the most promising first-generation and minority undergraduates seeking a PhD. This multifaceted approach to recruitment and admissions has enabled the enrollment sea change within the Graduate School.

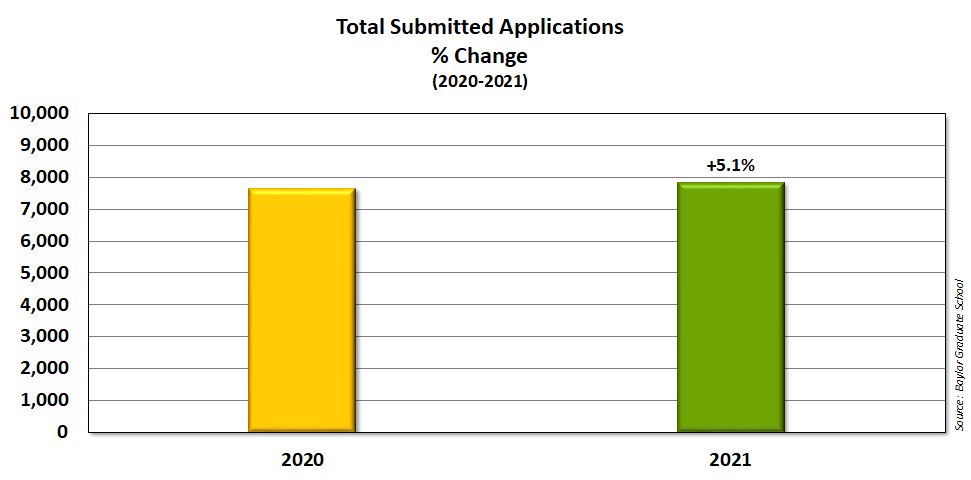

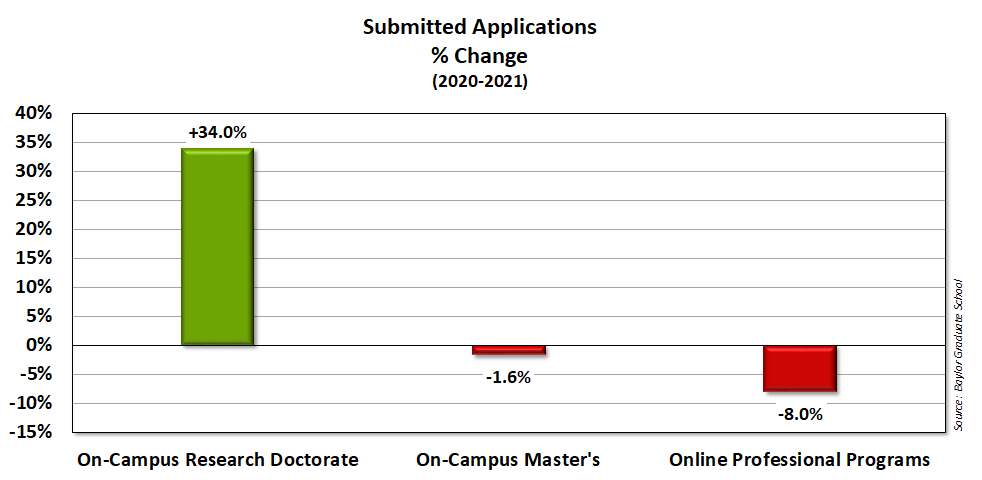

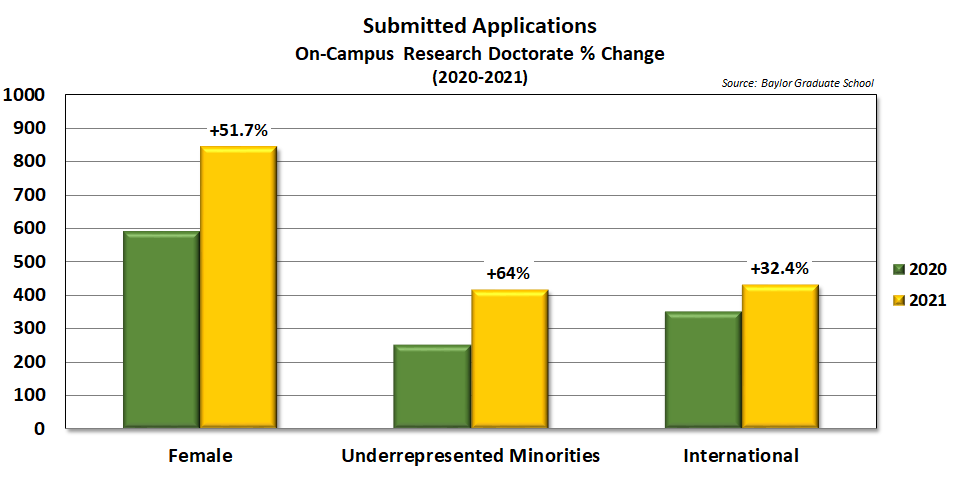

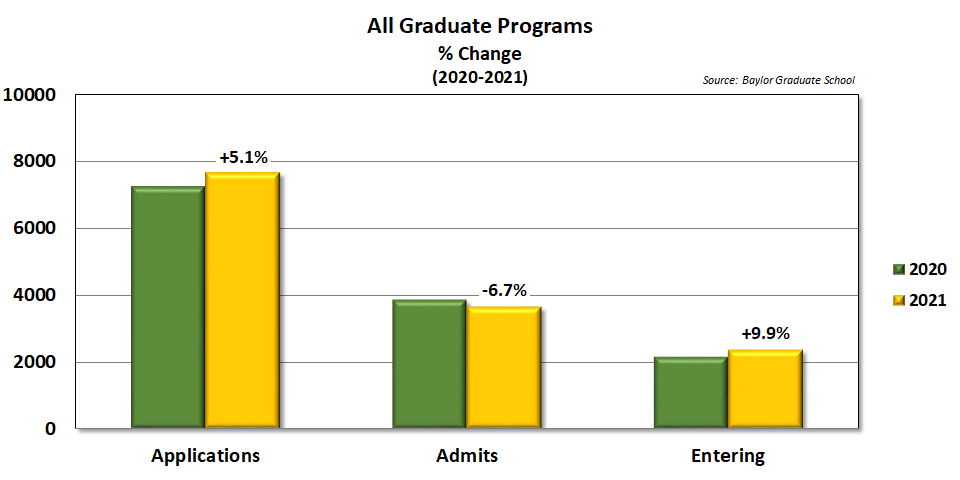

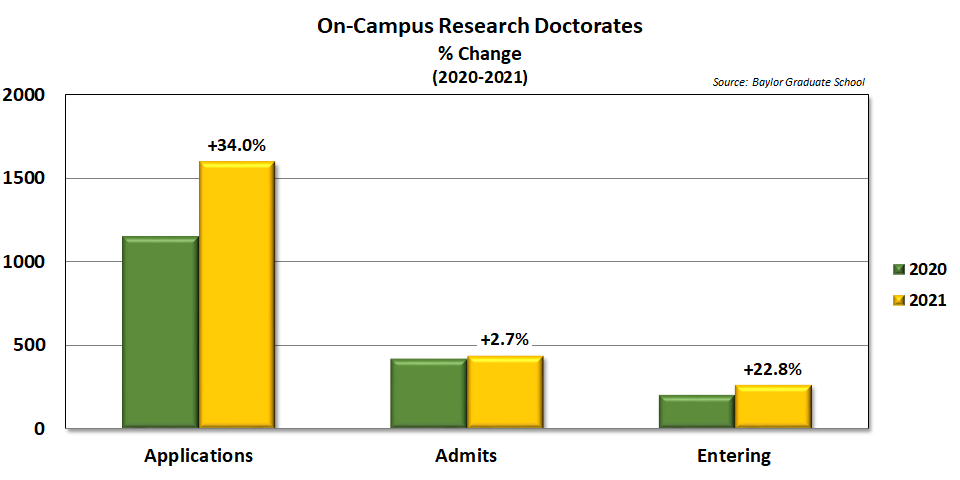

The results? Overall applications increased by just over 5%. Yet unlike enrollment, this increase came not from our professional and masters’ programs but from our on-campus research degrees, which grew by a third. The minor decrease in on-campus master’s applications reflects our R1-oriented decision to prioritize PhD programs rather than traditional MS and MA programs. The larger decrease in online programs is surprising, but likely driven by more targeted recruiting for our online MPH program and a decrease in applications to public health fields more broadly. The increase in on-campus research doctorates is the welcome result of the new set of R1-oriented recruitment initiatives described above. Many programs contributed to this increase, especially Biology, Chemistry and Biochemistry, Environmental Science, Geology, Religion, and both Psychology programs (PhD and PsyD).

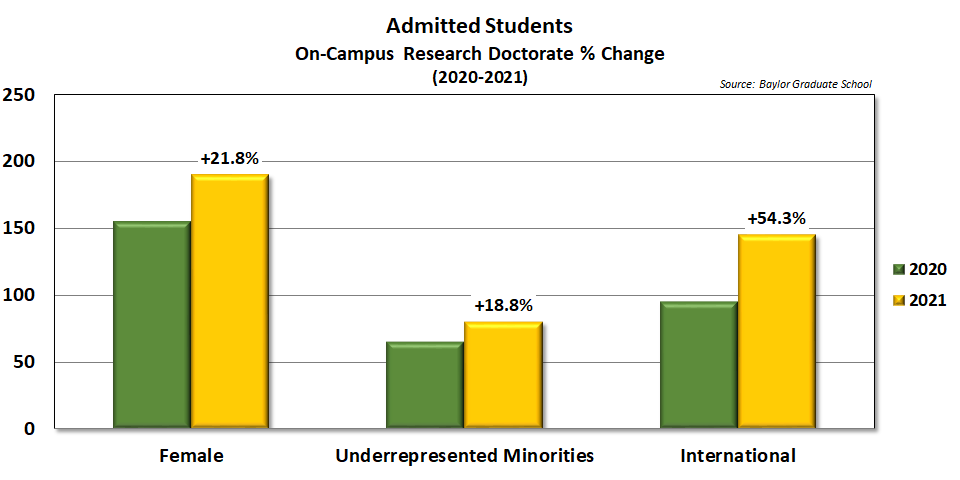

Our on-campus research programs also saw a significantly more diverse pool of applicants, with the number of female, minority, and international applicants each increasing substantially. The last of these is surely helped by the ease of COVID restrictions at the federal level. The first two are likely the result of the recruitment efforts described above.

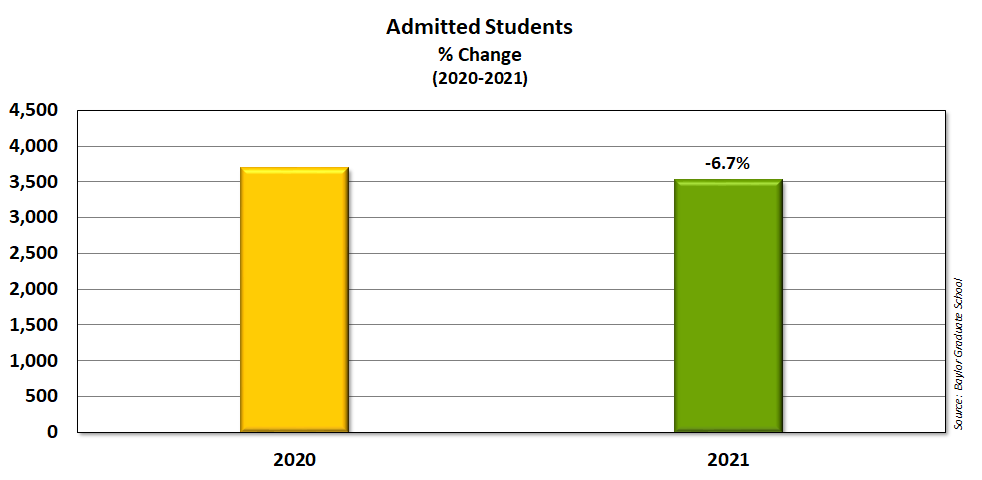

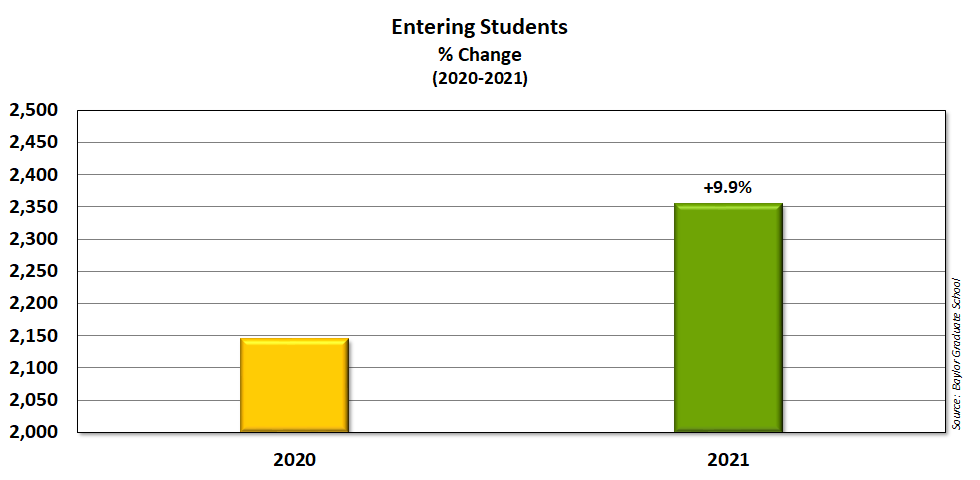

Did more applicants lead to more students? No; rather it led to more selectivity. As total applications continued to grow, the number of admitted students (those invited to enroll) fell by nearly 7%. However, the number of entering students (those who enrolled) rose by nearly 10%. Thus, while our overall acceptance rate decreased from 53% to 47%, our yield rate increased from 56% to 66%. This means that the Graduate School has become more selective while also becoming more attractive.

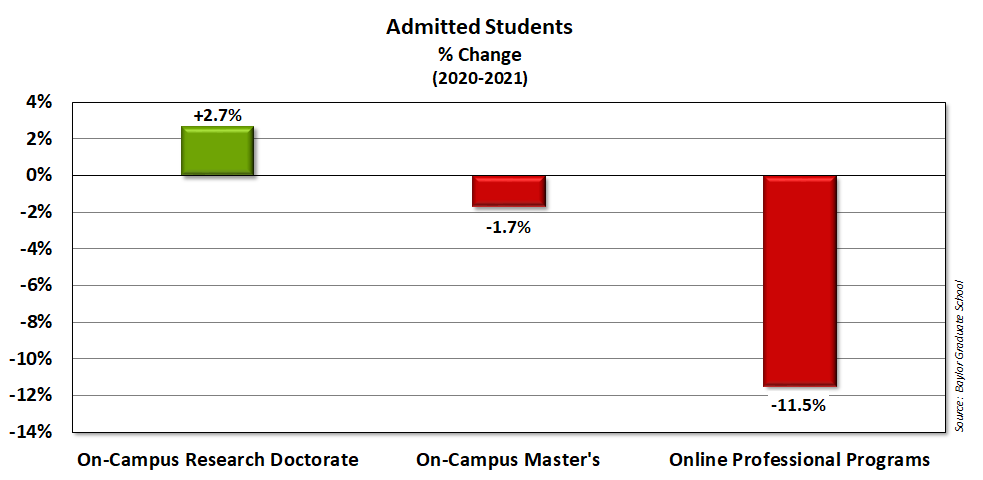

These positive changes were the result of two factors: first, a notable decline for online programs due to the strategic rightsizing of our online MPH program; second, significantly increased selectivity among our residential research programs, with our acceptance rate falling from 31% to 24% and yield rate increasing from 50% to 60%.

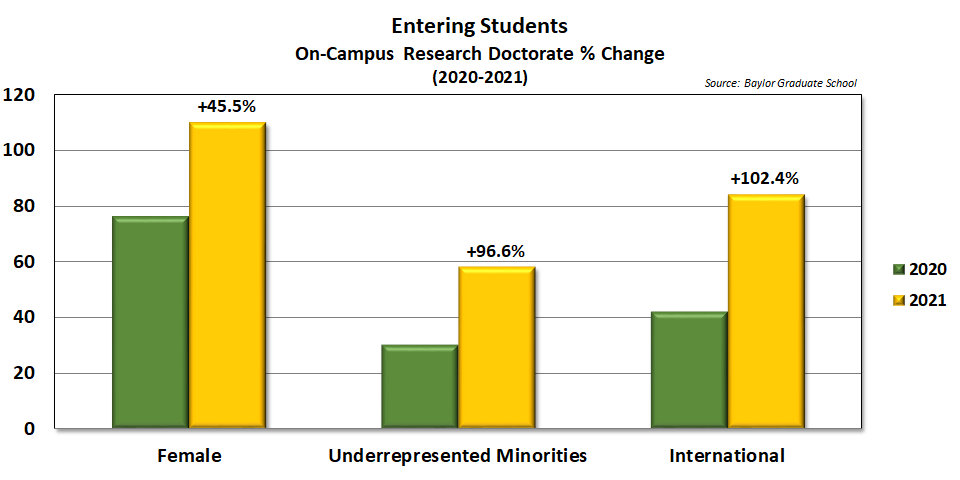

Another positive development: with the increased diversity in applications came greater diversity in admitted students. Although our on-campus research programs saw only a modest increase in acceptances (2.7%), there were double-digit increases in the number of offers made to female, international, and minority applicants.

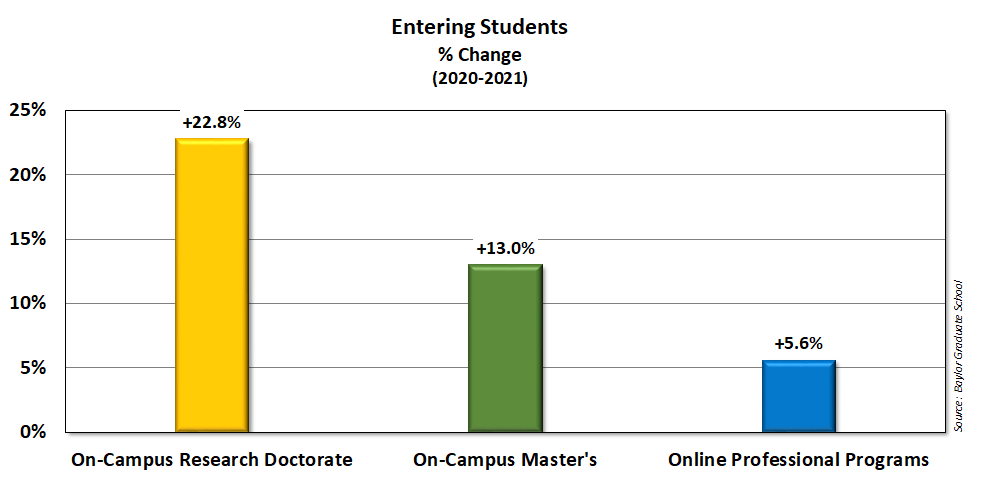

What about those who accepted our offers? Again, though we admitted fewer students in 2021, the number who accepted their offers increased by 10%.

The increase was shared by programs in each category, but our on-campus research programs saw the largest percentage growth, bringing in nearly a quarter more students than the previous year. As with applications and acceptances, we also enrolled a significantly more diverse cohort than the previous year. International students increased by the largest percentage, but that growth was nearly matched by the percentage of under-represented minority students, a group comprised exclusively of domestic students.

One final observation: Baylor’s traditional makeup with graduate students comprising only 15% of the overall student body is uncommon among research universities. Most have more balance between graduates and undergraduate, with some of the most prestigious having graduate students in the majority. Thus, the recent growth within the Graduate School, equaling now 25% of total enrollment, provides one more indication of our ongoing transformation into a preeminent Christian research university. Most of this growth has been in online and professional programs. But there have also been significant changes on the ground, making for a larger, more diverse, more research-focused, and more STEM-oriented residential student body.