After Graduation

Life After Graduation

Beth Allison Barr, Associate Dean for Professional Development

1951 marked the launch of Baylor’s first doctoral program—a PhD in English. Career aspirations for these early graduate students were straightforward: they were preparing for faculty positions in academia. More than seventy years later, Baylor boasts 28 on-campus research doctorate programs as well as an additional 8 professional and on-line doctoral programs. The landscape of our doctoral programs looks rather different than it did in 1951, which means the landscape of helping graduate students prepare for life after graduation must look different too.

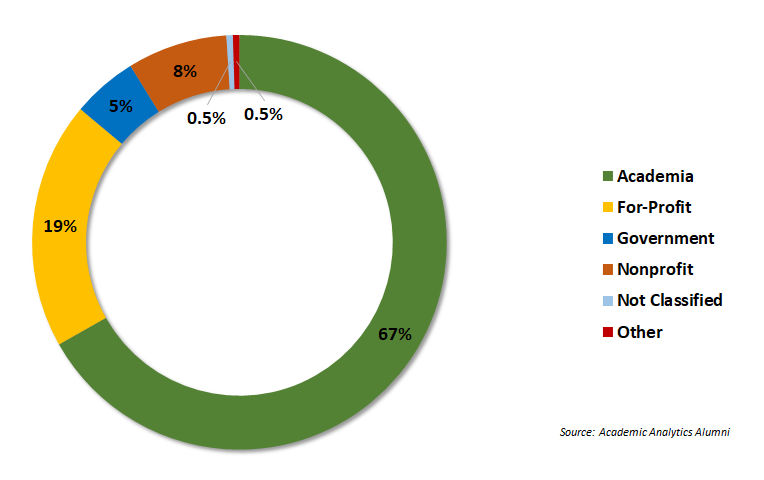

Figure 1: Placement for Recent PhD Graduates

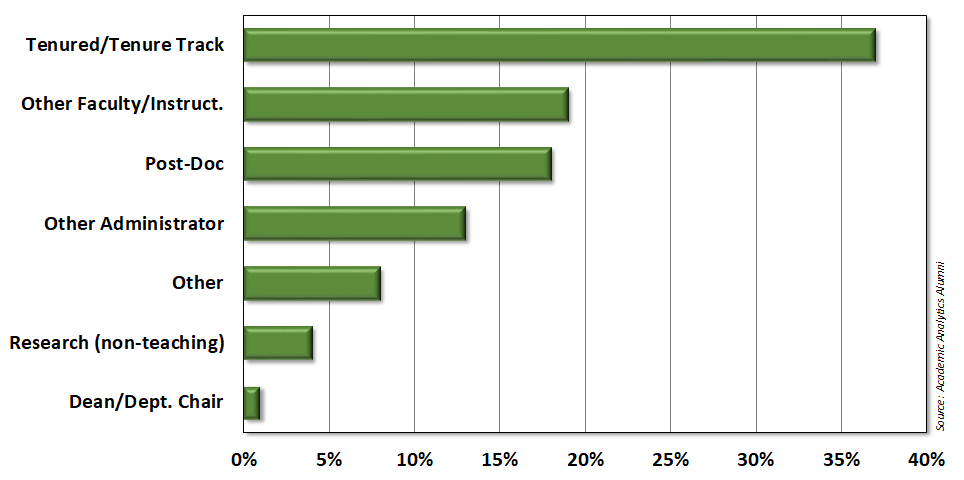

Figure 2: Occupations in Academia (Baylor Doctoral Graduates)

In general, Baylor graduate students do well on the job market. The Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED), which is administered by the National Science Foundation and offered nationally to all PhD students at graduation, shows that our research doctorates surpass peer institutions in both overall student placement as well as student placement within academia. However, the SED only provides an overview of general trends; it does not provide specific information about either students or programs. Three years ago, the Graduate School partnered with Academic Analytics to gather more specific data on life after graduation for our PhD students. What we have found matches the SED data: Baylor graduate students do well on the job market.

More specifically we found that our current research doctorate students, especially those in the humanities and social sciences, have research aspirations similar to their 1950s English graduate student peers. The Academic Analytics Alumni Insight data shows that between 2016 and 2021, 66.8% of our employed students were in academia (Figure 1) and the majority of these were in tenured and tenure-track positions (Figure 2). Yet, unlike their 1950s English graduate student peers, the academic job market these students face is more difficult. For several years, the Graduate School has offered an array of workshops to better prepare doctoral students for the academic job market—including workshops on developing CVs, preparing for interviews, and even mock interview sessions. Just last year, however, the Graduate School—with the support of the Provost’s Office and in collaboration with the College of Arts and Sciences, the Honors College, and the School of Education--launched a new initiative to prepare students for the job market: the Postdoctoral Teaching Fellowship Program. This program aligns Baylor with peer and aspirant universities such as the University of Notre Dame and Penn State, making our recruiting offers more competitive as we vie for top students. It also encourages our students to graduate within a timely manner, as (beginning in 2023) only doctoral students who complete their degrees within 5 active years will be eligible to apply.

But mostly the Postdoctoral Fellowship Teaching program equips Baylor graduate students for academic vocations. In addition to benefiting from a full-time salary with benefits, travel funds, and additional mentoring (a reading and discussion group hosted by the Graduate School), these fellows gain a year of job security, significant teaching experience, and breathing space after completing the PhD to allow more time to prepare for the job market—all of which significantly strengthen the competitiveness of our students. Kevin Gardner, the current chair of the Baylor English department, recently noted that the three postdoctoral teaching fellows in his department not only received teaching experience (each carrying a 4-4 load) but also received some of the highest scores on departmental teaching evaluations. As he wrote in an email to the Graduate School, “I wanted to let you know how proud I am of the English department’s three postdoctoral teaching fellows, Holly Spofford, Ben Rawlins, and Luke Mitchell. At the end of each semester, I compile for the dean’s office a report on the student evaluations earned by our postdoctoral teaching fellows (as well as our adjunct lecturers). I study the evaluations for each course these instructors taught in the preceding semester, and then note in my report whether the evaluation is ‘noticeably above,’ ‘very similar to,’ or ‘noticeably below’ the average of the comparison group courses. Of the twelve classes taught by our three postdocs, ten of them received a ‘noticeably above’ rating. That’s some consistently impressive teaching by our postdocs. I’m grateful to the provost and our graduate dean for supporting this teaching program, and I’m very proud of our fellows’ contribution to great teaching at Baylor!” These postdoctoral teaching fellows are entering a highly competitive job market with not only the experience they need, but also proof of their classroom excellence. Currently, we have eight postdoctoral teaching fellows at Baylor. Our goal is to continue expanding this program to meet the needs of our expanding PhD population.

Unlike English PhD students in the 1950s, more and more of our students do not aim for academic jobs. The growth of our online and professional programs as well as the changing interests of many research doctorate students is changing the career outcomes of our graduates. Already almost 1/3 of the jobs of our research doctoral graduates are outside of academia—in industry, for the government, and for non-profits. Moreover, while the vast majority of these continue to live and work within the United States, 29 have found international employment in 17 different countries—China, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, South Korea, Switzerland, Greece, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Lebanon, Nepal, Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. The Graduate School aims to equip these students just as well as their academically inclined peers. First, the Graduate School has increased our number of GPS workshops that prepare students for a more diverse job market, including providing Alternate Academic (Alt-Ac) Career podcasts continuously available online as well as workshops providing guidance for finding jobs in industry, government, and non-profit sectors. Second, we have partnered with Career Services to reach out to our non-professional graduates each semester, inquiring if they are interested in diverse job opportunities outside of academia. For those who are interested, Career Services provides individual guidance to help students locate job opportunities and prepare for interviews. Our goal is to continue expanding this partnership with Career Services to make sure all our students receive the assistance they need for life after graduation.

Third, the Graduate School has realized that to help our students navigate an increasingly diverse vocational job market we need to equip graduate faculty to mentor students pursuing jobs outside the academia. This past year the associate dean of professional development, Beth Allison Barr, led graduate program directors in a reading group discussing The New PhD: How to Build a Better Graduate Education. One of the points authors Cassuto and Weisbuch emphasize as essential for improving PhD programs is increasing awareness among graduate faculty that academia is often not the end goal for our students. “If we wish to commit to a more influential PhD,” Cassuto and Weisbuch write, “we need to map a route from the long-held, narrow goal of using the PhD to restock the faculty to a new PhD that will lend expertise to academia and other social sectors at the same time” (p. 143). Along with the GPD reading group, the Graduate School has also launched a graduate student/graduate faculty advisor agreement. Again, this aligns us with R1 peers such as the University of Michigan and Notre Dame. The Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan has found that “students with good mentors are more likely to have productive, distinguished, and ethical careers that reflect credit on the mentors and enrich the discipline. Effective mentoring helps ensure the quality of research, scholarship, and teaching well into the future.” Effective mentoring also opens conversations early in the relationship between students and faculty about the goals of the student. Instead of assuming graduates will be moving into academic positions, faculty will learn that students are interested in pursuing career diversity and will be able to begin helping build networks and shape research goals that will provide students with greater vocational options.

The landscape of graduate education has shifted considerably since Baylor admitted the first PhD candidates in English in 1951. But Baylor’s commitment to the success of our students beyond graduation remains just as strong as it was more than 70 years ago.